Garden Journal

I watched the elm for many years.

It stood tall and pristine, a straight trunk over fifty feet high and nearly two feet wide, and I knew what was coming. Dutch elm disease doesn’t rush; it arrives slowly—a yellowing branch, then another—thinning the crown and taking branches one by one. Each season, I examined it more closely—not just for its decline, but for its shape, its structure, and what it had already made.

A childhood memory from my dad’s greenhouse, where a single jade leaf quietly taught me what propagation — and vocation — could mean.

Hortiwijk grew from a lifelong wonder at watching seeds become something more. Shaped by family, horticulture, and a deep respect for the land, this space exists to share what careful observation can teach us—about plants, about place, and about our responsibility to tend what we’ve been given.

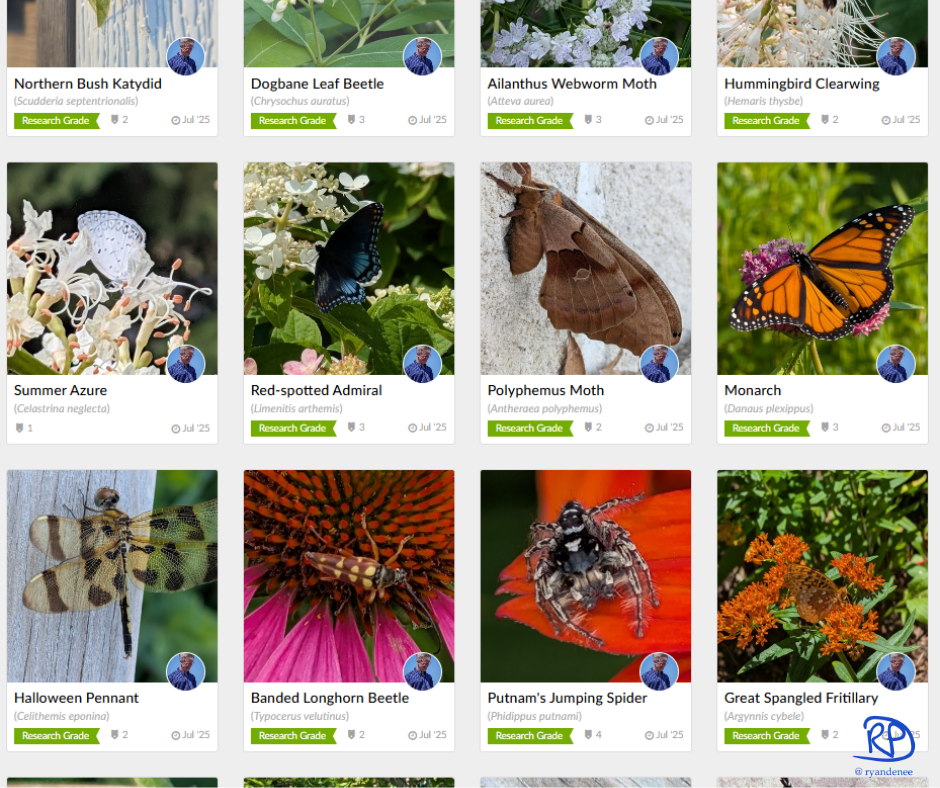

Bio Profiles

I usually notice this one only after it has already stopped moving.

Pressed flat against bark or siding, the wings held open and still, the moth looks less like an insect and more like pattern—something woven into the surface itself.

Sometimes weeks pass before spring feels believable.

When the forecast still calls for single digits Fahrenheit—or dips toward –20°C—and winter hasn't loosened its grip, my mind is already listening for peepers, one of the first signs that spring has finally arrived.

That thin, rising chorus drifting from ditches, vernal pools, and low woods is one of the earliest true signals that the year is turning.

When we walk through a garden, the first things we notice are the obvious ones—the trees, the shrubs, the flowers. In most gardens, these are known. They’re labeled, recognized, or at least familiar. We say, oh, that’s this tree or that flower. Even if we don’t know the Latin name, we usually know a common one—sometimes local, sometimes idiosyncratic, sometimes surprisingly creative.